특발성 폐 섬유화증의 병인 및 최신 진단 기준

Pathogenesis and New Diagnosis Guideline of Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis

Article information

Trans Abstract

Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) is a progressive and fatal fibrotic lung disease in many patients. In spite of extensive research for many decades, the exact pathogenesis of IPF is unknown. At recent, the role of alveolar epithelial cells has been focused in the initiation of IPF in terms of epithelial-mesenchymal transition, dysregulated Wnt signaling, and activation of transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β). The resulting excess collagen deposition and destruction of lung architecture by myofibroblasts and fibroblastic foci leads to the development of IPF. IPF can be diagnosed by typical high resolution chest tomogram (HRCT) or by multidisciplinary discussion based on the new guideline published on 2010. (Korean J Med 2013;84:481-488)

서 론

특발성 폐 섬유화증(idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, IPF)은 점점 나빠지며 치명적인 간질성 폐질환으로 알려져 있지만 여전히 정복되지 않은 질병으로 남아있다. 지난 수십 년간 병인을 밝히기 위하여 수많은 연구가 이루어져 왔으며 이들 연구를 바탕으로 새로운 개념이 많이 정립되었지만, 불행히도 현재까지 폐 섬유화의 정확한 원인이 알려져 있지 않다. 그렇지만 과거의 IPF는 염증성 폐 질환이라는 개념에서 기도상피세포의 손상이 중요한 병인으로 대두되고 있으며, 최근에 연구되는 epigenetics (후생학)까지 폐 섬유화에 관계한다는 것으로 연구가 발전되었다.

2011년도에 세계적으로 몇 개의 유관학회가 지금까지의 연구 결과를 바탕으로 IPF의 진단 및 치료 방침을 발표하였다[1]. 중요한 변화는 IPF에 합당한 임상양상과 전형적인 고해상도 흉부 단층 소견이면 폐조직 검사 없이 IPF로 진단할 수 있다는 것이다.

여기에서는 최근 새로이 알려진 IPF의 병인과 최근의 IPF 진단 방법에 대해서 기술하고자 한다.

본 론

병인

어떤 이유든 유전적 혹은 후생학적인 질병의 요인이 있는 사람에게 원인 물질에 노출 시 폐포상피세포(alveolar epithelial cells, AEC) 혹은 섬유아세포에서 transforming growth factor-β(TGF-β)를 활성화시키고, 이로 인하여 폐의 간질에 섬유화가 일어난다고 알려져 있지만 이 설명만으로는 폐 섬유화를 설명하기는 한계가 있다. 아마도 조절되지 않는 면역 기전(deregualted immune mechanism)과 계속해서 일어나는 염증성 반응에 의해서 섬유화가 진행될 것으로 판단된다[2].

여기에서는 섬유화에 관계하는 폐포상피세포의 역할, 세포의 변환(cellular plasticity), 후생학에 관해서 기술하고자 한다.

폐포 상피 세포

흡연, virus 감염, 흡인 등 주위 환경이 AEC에 상처를 주면 AEC가 활성화되는 것이 IPF 병인의 시초라고 할 수 있다[1,3]. AEC가 활성화되면서 불적절한 세포 내 신호전달체계(dysregulation of signal transduction), 응고반응(coagulation pathway), epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) 등의 반응이 나타나면서 폐 섬유화가 일어난다[4-6]. EMT는 아래에서 다시 기술한다.

신호전달 체계의 이상(dysregulation of signal transduction)

Wnt는 “세포 파괴”에 중요한 역할을 하는데, 만약 활성화되면 세포 내의 β-catenin을 증가시키고, 이로 인하여 세포의 apoptosis가 억제되고 활성화가 일어난다[7]. IPF 환자의 fibrobastic foci에서는 non-specific interstitial pneumonia (NSIP)환자의 조직에서는 보이지 않는 β-catenin이 핵 내에서 많이 발견되는데[8], 이 현상도 IPF 환자에서는 Wnt가 활성화되어 있다는 것을 시사하는 소견이다. 특히 최근 연구에 의하면 TGF-β 자체가 Wnt를 활성화시키며[9], 그리고 Wnt의 활성화는 TGF-β에 의한 섬유화에 필요하다는 것이 밝혀졌다[10]. 따라서 Wnt가 섬유화의 중요한 매개체임을 알 수 있고, 이의 활성화를 억제할 수 있으면 섬유화를 조절할 수 있을 것으로 추측된다.

Phosphatase and tensin homologue (PTEN)은 세포의 apoptosis에 관계하는데[11], IPF 환자의 fibroblastic foci 내의 근육섬유모세포(myofibroblast)에서 PTEN의 발현이 감소되어 있으며, 이는 근육섬유모세포의 apotposis가 억제되어 섬유화를 유발한다는 것이다[12].

응고 반응

상피세포의 손상은 TGF-β의 활성화와 PAI-I 합성의 증가를 통하여 plasmin 활성화를 억제시키고, 이어 섬유소용해성(fibrinolysis)을 억제하여 섬유화를 촉진한다. 이는 TGF-β 활성화가 일어나면 상피 세포의 PAI-I 합성 증가가 일어나는 것이 확인되었으며[13], bleomycin에 의한 동물모델에서 plasmin 활성화를 억제시키면 섬유화가 나타나는 것으로 알 수 있다[14]. 상피세포가 손상을 받으면 활성화된 factor X 합성이 증가되고, 이는 TGF-β 활성화를 증가시켜 근육섬유모세포의 분화를 촉진시킨다[15]. 따라서 상피세포 손상에 의한 응고반응이 섬유화의 병인에 관계할 수 있다.

세포의 변환(cellular plasticity)

폐의 치유 과정에서 섬유화가 일어나는데, 이 섬유화에 중요한 역할을 하는 세포가 궁극적으로 근육섬유모세포이며, 이 세포는 섬유모세포(fibroblast)와 평활근(smooth muscle) 세포의 성질을 모두 갖고 있다. 근육섬유모세포가 어디에서 기원하고 어떤 기전으로 나타나는지 알아본다.

상주하는 섬유모세포의 활성화

가장 잘 알려져 있는 것은 폐의 간질에 있는 섬유모세포가 TGF-β, PDGF 등의 성장인자(growth factor)에 의해 활성화된 근육섬유모세포로 분화되고 증식된다는 것이다[16,17]. 최근의 흥미를 끄는 가설은 기질(matrix) 자체가 섬유모세포를 근육섬유모세포로 분화시킨다는 것이며, 그 기전은 섬유모세포가 기질에 느슨하게 붙어있다가 상처가 치유되는 과정에서 기질이 딱딱해지면 근육섬유모세포로 분화된다는 것이다[18]. 이런 현상은 기질이 딱딱해지면서 integrin의 세포질 도메인에 의해 TGF-β가 활성화되는 것이며 주로 αvβ3와 αvβ5를 통해서 이루어진다[19]. 하지만 이 가설에 대해서는 지속적인 연구가 필요하다

Epithelial-mesenchymal transition

EMT는 상피세포가 상피세포의 특징이 없어지면서 중간엽세포(mesenchymal cell)의 특징을 갖는 과정을 말한다[20]. 생체 연구에서 TGF-β를 과발현시키는 동물 모델의 폐[21]와 그리고 bleomycin으로 처리한 동물의 폐[22]에서 상피세포의 특징인 E-cadherin과 surfactant-protein C의 표현이 감소되고 중간엽세포의 특징인 α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA)과 S1000-A4의 표현이 증가되는 상피세포가 많아진다는 것이다. 또한 IPF 환자의 조직의 폐 상피세포에서도 α-SMA과 폐포 상피세포의 특징인 pro-surfactant protein-B가 동시에 발현된다[20].

Endothelial-Mesenschymal transition

Bleomycin으로 유도된 폐 섬유화 모델에서 폐의 혈관내피세포에서 유래된 섬유모세포가 발견되는데 이는 endothelial-mesenchymal transition에 의해서 분화되었으며, 섬유모세포의 약 16%가 혈관내피세포에서 분화한 것으로 추측된다[23].

후생학적 측면

MicroRNA

MicroRNAs (miRs)는 21-22개 정도의 뉴클레오티드로 구성되는 non-coding RNA의 일종으로 전사 후의 유전자 발현(post-trasnscription)을 조절하는 것으로 알려져 있으며[26], messenger RNA의 파괴, 혹은 전사(translation)를 억제시켜 단백질 합성을 억제시킨다. IPF 환자에서 처음으로 연구된 miR은 let-7으로 TGF-β의 신호전달 체계의 하나인 smad-3와 결합한다. IPF 환자의 조직에서 정상인보다 발현이 적으며, 발현이 적을수록 FVC도 감소하는 것으로 보고되었다[27]. Let-7을 억제시키는 antagomir를 투여하면 섬유화가 진행되며, EMT의 중요한 조절인자인 high mobility group AT-hook 2[28]의 발현이 증가된다는 것이다. 그러나 현재까지 let-7을 투여하면 섬유화가 억제되거나 혹은 개선되는 연구는 없으며 어떤 경로를 통하여 섬유화의 억제를 가져오는지는 알 수 없다. 이외에도 섬유화를 억제시킬 수 있는 miRs에는 miR 17-92 [29], miR-200 [30], 그리고 섬유화를 유발하는 것은 miR-21 [31], miR-154 [32], miR-155 [33]가 있다. IPF 환자에서는 증명된 바 없지만 TGF-β1 합성을 억제할 수 있는 miR-744[34], 663 [35]도 폐 섬유화에 관계할 것으로 추측되고 있다. 이외에도 폐 이외의 여러 장기 및 동물실험에서 섬유화에 관계하는 여러 miRs가 알려지고 있다.

DNA methylation

DNA methylation은 주위 환경이나 담배와 같은 물질에 노출시 DNA의 cytosine이 methylation되는 것으로 이로 인하여 DNA 복제가 억제된다. 만약 섬유화를 억제시키는 유전자의 promoter 부분에 methylation이 발생하면 섬유화가 일어날 것이다. 일부 IPF 환자에서 Thy-1 promoter 부분에 methlyation이 있는 것이 확인되었다[36]. Thy-1은 폐 섬유아세포의 근섬유아 세포로의 분화를 억제하는 단백질[37]로 IPF 환자의 폐 조직 내 fibroblastic foci에서 감소되어 있다[38]. IFN-γ-inducible protein 10 (IP-10)이 감소하면 섬유화가 증가하는 것이 알려져 있다[39]. IPF 환자의 섬유아세포에서 IP-10 promoter 부분의 methylation이 일어나는 것이 증명되었다[40]. 이외에도 methylation chip을 이용한 연구에서 정상인과 IPF 환자 사이에 여러 유전자의 methylation 차이를 확인하였다[41,42]. 이러한 일련의 실험들은 DNA methylation이 IPF의 병인에 중요하다는 것을 시사하는 소견이라고 하겠다.

진단[1]

IPF가 의심되는 경우 진단 방법은 그림 1을 따른다. 진단에서 중요한 점은 고해상도 흉부 단층 촬영(high resolution chest tomogram, HRCT)과 조직 검사가 명확하지 않을 때는 임상, 영상의학, 병리 의사가 모이는 다자 토의(multidisciplinary discussion)를 통하여 진단한다는 것이다. 그리고 HRCT에서 전형적인 소견을 보이는 경우는 조직 검사 없이 IPF로 진단할 수 있다.

IPF의 진단 기준은 다음과 같다. 첫째, 간질성 폐질환을 일으킬 만한 알려진 원인(환경성 노출, 교원성 혈관 질환, 약제 독성)이 없어야 하며, 둘째, 폐조직 검사를 하지 않은 환자에서는 HRCT에서 전형적인 통상성 간질성 폐렴(usual interstitial pneumonia, UIP)을 보여야 하며 셋째, 폐 조직 검사를 한 경우에는 HRCT와 폐조직 소견의 형태를 보고 결정해야 한다.

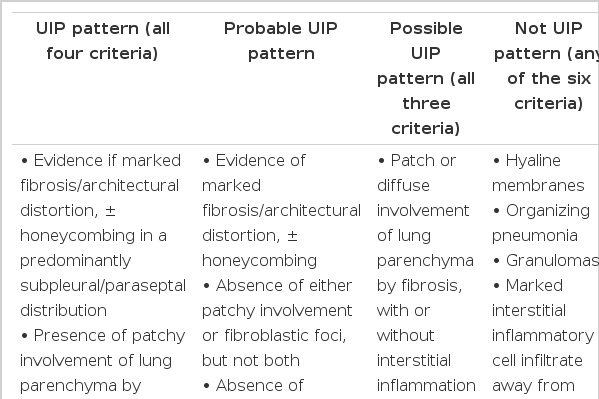

IPF가 의심되는 경우에 HRCT를 시행하여 UIP 모양이면 조직 검사 없이 IPF로 진단할 수 있다. UIP 모양은 그림 2와 같이 폐의 아래쪽 그리고 변연부에 주로 병변이 있고(subpleural basal predominance), 벌집 모양(honeycoomb), 망상의 음영(reticular densities)이 있으면서, UIP와 맞지 않는 소견(Table 1의 세번째 열)이 없을 때를 말한다. Possible UIP는 그림 3과 같이 전형적인 UIP 모양에서 벌집 모양이 없는 경우이며 이런 경우는 IPF 진단을 위해서는 조직 검사를 반드시 시행해야 한다(Table 1).

High-resolution tomography demonstraing UIP pattern. Extensive honeycombing (arrow), reticular abnormality (arrow head), basal and peripheral predominant lesion are shown in axial (A) and coronal image (B).

High-resolution tomography demonstraing UIP pattern. Reticular abnormality (arrow), basal and peripheral predominant lesion are shown in axial (A) and coronal image (B).

폐 조직 검사에서도 표 2와 같이 UIP pattern, possible UIP, probable UIP로 나눈다. 전형적인 UIP 형태는 심한 섬유화 소견과 동반된 구조의 변형, 섬유화에 의한 patchy involvement, fibrobasltic foci 등이다.

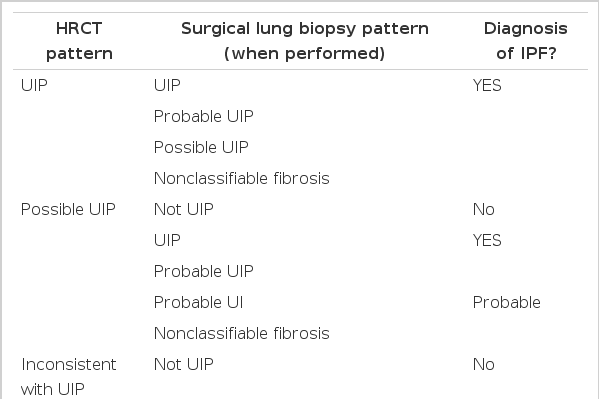

HRCT와 조직 검사를 종합하면 표 3과 같다. HRCT에서 UIP pattern을 보이면 조직 검사에서 전형적인 UIP pattern이 아니어도 IPF로 진단할 수 있다. HRCT에서 probable UIP인 경우는 조직 검사에서 UIP pattern이거나 혹은 probable UIP인 경우는 UIP로 진단할 수 있다.

Combination of high-resolution computed tomography and surgical lung biopsy for the diagnosis of IPF (requires multidisciplinary discussion)

기관지폐포 세척술과 경기관지 폐 생검은 진단을 위하여 대부분의 IPF 환자에서 추전되지 않는다.

결 론

현재까지도 IPF의 발생 원인은 알려져 있지 않지만, 여러 연구의 발달로 병인을 밝히는 데 많은 발전이 있었다. 특히 후생학 연구의 발달로 IPF의 병인을 DNA부터 전사 후(post-transcription)의 변화까지 알 수 있게 되었다. 하지만 섬유화에 가장 중요한 TGF-β 활성화만으로는 IPF의 병인을 모두 설명할 수 없으며, 섬유화에 이르게 하는 여러 세포와 단백질이 상호 활성화시키면서 섬유화가 계속 진행하는 것으로 보이며, 이에 대한 연구가 진행되어야 할 것이다.

병인과 달리 진단은 많은 발전이 있었다. 특히 최근에 발표된 지침을 통하여 폐 조직 검사 없이도 진단할 수 있는 근거를 마련하였으며, IPF의 진단을 위하여 관계하는 과간의 상의를 통하여 진단할 수 있게 되었다.