젊은 여성에서 불명 열의 형태로 나타난 인위열 1예

Factitious Fever Presenting as Fever of Unknown Origin in a Young Woman: A Case Report

Article information

Trans Abstract

A 23-year-old woman presented with refractory anemia and a 1-month history of relapsing fever. The patient had been followed up at another hospital for fever of unknown origin and refractory anemia for 2 years. Upon admission to our hospital, repeated body temperature measurements and a nurse’s inspection revealed that the patient had been artificially heating the external auditory canal where the temperature was measured to simulate fever. No temperatures exceeding 38℃ were recorded after the nursing staff removed objects capable of altering measurements, confirming factitious fever as the cause. We report this case to highlight the importance to clinicians who care for patients with fever of unknown origin despite careful and appropriate evaluation.

INTRODUCTION

Fever of unknown origin (FUO) is defined as a temperature of ≥ 38.3℃ for at least 3 weeks without a definite cause [1]. Patients with FUO that resolves after more than 4 weeks have a good prognosis, and almost 51-100% of these patients fully recover. Factitious fever, which is challengine to indentify unless confirmed through suspicion, is one of the differential diagnoses of FUO [2-4]. A delay in diagnosis may increase not only medical costs, but also the risk of self-injury. Herein, we present a case of factitious fever in a 23-year-old woman with a 2-year history of recurrent fever.

CASE REPORT

A 23-year-old woman presented with a 1-month history of fever. Additionally, she had refractory anemia and recurrent fever for 2 years. She was originally seen at another tertiary hospital, where she had been admitted 10 times during the past 2 years because of recurrent fever, anemia, dysuria, and seizure-like movements, which occurred 6 months after the start of follow-up. As part of the comprehensive assessment for her condition, esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD), colonoscopy, bone marrow (BM) examination, Technetium-99m dimercaptosuccinic acid kidney scan, voiding cystourethrogram, and electroencephalogram (EEG) were performed during the past 2 years, but no definitive cause was found. One year after follow-up and during her sixth admission, she was diagnosed with acute hepatitis C and has been maintained on sofosbuvir since then. The 10th admission to the first hospital was due to general weaknesses. Laboratory tests revealed elevated liver enzyme levels. Therefore, sofosbuvir was temporarily discontinued. Once her condition improved, sofosbuvir treatment was resumed. However, myalgia, nausea, and vomiting persisted despite normal blood parameters. Hence, further evaluation, including psychiatric consultation, was planned. However, the patient was discharged at her request. The patient presented to a secondary hospital with dysuria, nausea, and vomiting the day after discharge from the previous hospital. Blood testing confirmed anemia (hemoglobin, 7.9 g/dL), and the patient complained of fever. Hence, the patient was transferred to a tertiary general hospital for further evaluation and management.

Upon admission, repeat blood tests revealed anemia (hemoglobin, 7.9 g/dL). EGD and colonoscopy were performed to rule out gastrointestinal bleeding, but the results were negative. A fever of up to 38℃ and anemia persisted during hospitalization, and cervical lymph node enlargement was observed. Therefore, a cervical lymph node biopsy was performed. BM biopsy was repeated but showed normocellular marrow. The patient was then transferred to our hospital for further evaluation.

Upon admission to our hospital, her vital signs were stable, and she was afebrile (36.5℃). Her numerical rating scale (pain) score was 3-4 points for abdominal pain. The Foley catheter from the previous hospital was retained for dysuria, and the abdominal pain persisted. However, the central venous catheter (CVC) that was inserted at the second hospital was removed on the day of admission because of a history of multiple catheter-related bloodstream infections during previous hospitalizations. A peripheral blood smear revealed normocytic normochromic anemia, and blood testing revealed a hemoglobin level of 8.0 g/dL. Liver and renal function tests revealed normal results. Levels of inflammatory markers, such as erythrocyte sedimentation rate, C-reactive protein, and procalcitonin, were also within the normal ranges.

On the second day of admission, fever of 38℃ along with persistent abdominal pain were noted. Abdominal computed tomography (CT) was attempted but was unsuccessful, as contrast agents could not be infused due to poor peripheral vascular condition. Hence, a CVC was inserted on the fourth day of admission to enable the patient to undergo abdominal and cervical CT scans, and no findings related to the possible causes of fever or abdominal pain were found. EGD performed on the same day revealed erosive gastritis. Blood cultures were performed to rule out typhoid fever. Ceftriaxone was administered as an empirical antibiotic. On the seventh and eighth days of admission, which were also the third and fourth days of antibiotic therapy, respectively, fever of ≥ 39℃ was noted; this was inconsistent with typhoid fever. Therefore, antibiotic therapy was discontinued, and the CVC was removed on the ninth day of admission. Tuberculosis-specific antigen-induced interferon-gamma test revealed a negative result. No organisms were identified in the blood, urine, or stool cultures.

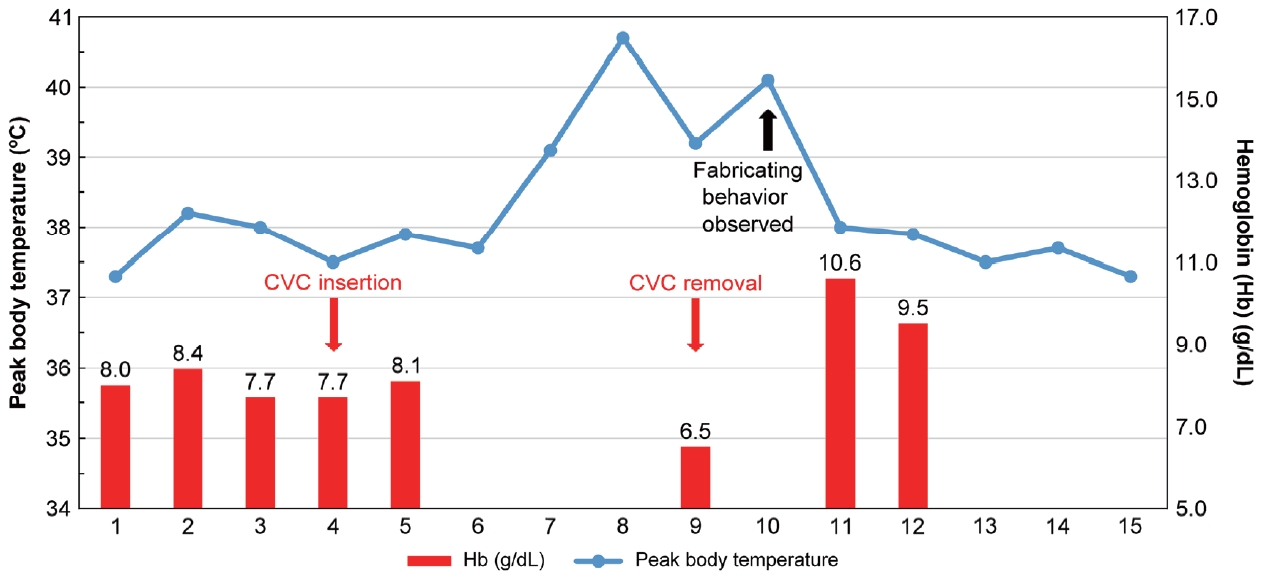

On the ninth day of admission, repeat blood testing revealed that her hemoglobin level had decreased to 6.5 g/dL (Fig. 1) from 8.1 g/dL on the fifth day of admission, prompting the transfusion of red blood cells. There was no evidence of external or internal bleeding that accounted for the decreased hemoglobin level. Additionally, BM biopsy slides from the previous two hospitals were reviewed, and no specific findings were detected. Whole-body fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography/computed tomography did not reveal any significant relationship between fever and anemia. Except for oral vancomycin, all medications were discontinued to rule out the possibility of drug-induced hyperthermia, and symptomatic management of fever was initiated.

Clinical course and transition of peak body temperature and hemoglobin level. CVC, central venous catheter; Hb, hemoglobin.

On the 10th day of admission, the patient’s stool tested positive for Clostridium difficile toxin B, and she was started on oral vancomycin. Autoimmune marker testing revealed no specific findings. In addition, the patient complained of high fever. Using a tympanic thermometer, the patient’s body temperature was monitored every 5-10 minute. Temperature decreased from 39℃ to 37.3℃ without antipyretics being administered. After an hour, she complained of fever. Therefore, the nurse rechecked her body temperature. The thermometer showed 38.9℃, which was an unusually rapid change from the temperature 1 hour prior. During this time, a nurse observed that the patient had placed something in her ear and removed it before complaining of fever. An investigation of the patient’s belongings revealed a metal nail clipper and tumbler containing hot water under her blanket. Therefore, items that may have affected her body temperature were removed, and the patient’s temperature was monitored for 5 days. Every time she complained of fever, the temperature was checked tympanically and orally. On the 15th day of admission, a body temperature of more than 37.5℃ was rechecked by a nurse. However, the peak body temperature was below 38.0℃ (Fig. 1), which rapidly decreased in less than an hour. On the 14th day of admission, seizure-like movements accompanied by stiffness of the extremities and eyeball deviation lasting for 10 minutes were first observed at our hospital. Convulsive movements of the extremities and memory loss were also observed. She was then referred to the Neurology Department, which stated that based on the pattern of her movements, there was a low possibility of an epileptic seizure. Subsequently, her condition stabilized and she was discharged on the 15th day of hospitalization. Admission to a psychiatric hospital for evaluation and management.

DISCUSSION

In this case, a factitious disorder, represented as factitious fever, was suspected because of the unusual pattern of fever, the patient’s behavior that could affect the tympanic temperature, and the oral temperature, which did not show a high fever.

The suspicion of a factitious disorder was further supported by the patient’s erratic behavior and seizure-like movements, which were first observed by the hospital staff in the previous hospital. Brain magnetic resonance imaging and cerebrospinal fluid analysis were performed at another hospital to investigate convulsive movements; however, there were no abnormal findings. The neurologist at the first hospital suggested possible malingering based on the above findings. EEG was also performed at another hospital. However, no epileptic waves were observed. In our hospital, based on a collaborative consultation with the Department of Neurology, we determined that there was a low possibility of patients having epileptic seizures. Factitious disorders are commonly accompanied by symptoms that require emergency treatment. In the present case, the patient complained of seizures.

Risk factors and a history of psychiatric issues are important for the diagnosis of a factitious disorder because this condition does not manifest with physical symptoms or physical diseases [5]. If not diagnosed, unnecessary medical costs and, most importantly, the possibility of permanent physical disability through self-injury may occur. In our case, the patient underwent several examinations, including EEG for seizure-like movements, endoscopy, and BM biopsy for fever and anemia. Additional tests for rare febrile diseases were also considered. Furthermore, she experienced catheter-related bloodstream infections and Clostridium difficile -associated disease, which were probably related to self-injury and the inappropriate use of antibiotics.

Factitious fever represents 1-10% of FUO cases and may be fraudulent or self-induced [6,7]. The manipulation of temperature measurements represents a fraudulent fever. Meanwhile, an infectious substance or pyrogen that has been consumed or injected can cause self-induced fever [8]. The patient had a history of frequent catheter-related bloodstream infections and repeated manipulation of the CVC while in hospital. However, it is more likely that the anemia-inducing maneuver was more effective than injecting an infectious pathogen. It is possible that the patient heated the metal nail clippers in hot water, which affected the tympanic temperature.

Because factitious fever is not associated with any specific febrile illness, it is difficult to diagnose this condition based on clinical signs and symptoms alone. Although patients with factitious disorders are usually young, female, and working in healthcare, it is clinically difficult to suspect and differentiate factitious fever in patients with the abovementioned characteristics based on the presence of unexplained fever [7]. Rather, the discrepancy between fever patterns or test results and the physical condition of patients with unexplained fever should be the main parameter when a factitious fever is suspected. Therefore, if unexplained fever persists in patients who have been appropriately examined and treated symptomatically, it is important to frequently assess their body temperature at several sites to specifically and accurately identify the fever pattern. Any discrepancies can serve as evidence to differentiate this condition from other febrile conditions. Physicians should be aware of the possibility of factitious fever as a cause of FUO. With careful inspection and suspicion, early diagnosis will not only prevent unnecessary use of healthcare resources, but also protect patients from harm or the development of actual physical illness, thus enabling them to receive appropriate treatment through collaboration with psychiatric specialists.

Notes

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

FUNDING

None.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conceived and designed the analysis: Woo Joo Kim.

Data collection: In Seon Kim, Ji Yun Noh.

Contributed data/analysis tools: Saemna Lee, Ji Yun Noh, Joon Young Song, Hee Jin Cheong.

Performed the analysis: Saemna Lee, Ji Yun Noh, Joon Young Song, Hee Jin Cheong.

Wrote the paper: Saemna Lee.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

None.