무증상 대장궤양으로 발현된 단형성 상피친화성 장 T-세포 림프종 1예

A Lethal Case of Monomorphic Epitheliotropic Intestinal T-Cell Lymphoma Presented as Asymptomatic Colonic Ulcer

Article information

Trans Abstract

Intestinal T-cell lymphoma is an uncommon type of non-Hodgkin lymphoma that primarily affects the gastrointestinal tract. Among the known subtypes, monomorphic epitheliotropic intestinal T-cell lymphoma (MEITL) is a particularly aggressive form characterized by poor prognosis and high mortality. Its rarity and diverse clinical presentations hinder clinical research and the establishment of standardized treatment protocols. Additionally, the treatment response and overall survival rates are typically very low. Herein, we report the case of a 70-year-old man who was referred for evaluation of an asymptomatic colonic ulcer that could not be diagnosed by colonoscopic biopsy but was finally identified as MEITL following surgical resection. Although the patient was diagnosed relatively early during clinical evaluation, treatment initiation was delayed owing to intestinal perforation. Several clinical findings should be considered when diagnosing MEITL. First, early diagnosis is necessary for prompt treatment. Second, gastrointestinal lymphoma should be suspected in patients with atypical or unexplained gastrointestinal findings. When endoscopic biopsy is feasible, like in this case, careful sampling is essential. Lastly, even with early diagnosed, prompt therapeutic intervention is crucial, as MEITL can progress rapidly.

INTRODUCTION

Primary gastrointestinal lymphomas account for approximately 4-12% of all non-Hodgkin lymphomas and 1-4% of all gastrointestinal tumor cases [1]. Monomorphic epitheliotropic intestinal T-cell lymphoma (MEITL) is rare and accounts for < 5% of all gastrointestinal lymphomas [2]. The low incidence and diverse symptoms of MEITL make clinical research and treatment standardization difficult [3]. MEITL is not known to be associated with celiac disease and has been reported predominantly in Asia, where the incidence of celiac disease is low [4]. It can occur in adults of any age, with a median age at diagnosis of 59 years (range, 23-89) [5]. MEITL occurs more commonly in men, with a male-tofemale ratio of 2:1 [5]. The most common site of involvement is the small intestine (80-90%), whereas involvement of the large intestine (< 20%), mesenteric lymph nodes (35%), and bone marrow (< 10%) is less common [3]. Most patients present with a single intestinal lesion; however, multiple lesions have been reported [3]. Additionally, with a low treatment response rate and an overall survival time of only 7 months, the prognosis of patients with MEITL remains poor [3]. Herein, we report the case of a 70-year-old man who was referred for an asymptomatic colonic ulcer that was initially nondiagnostic on colonoscopy but was ultimately confirmed as MEITL through surgical resection.

CASE REPORT

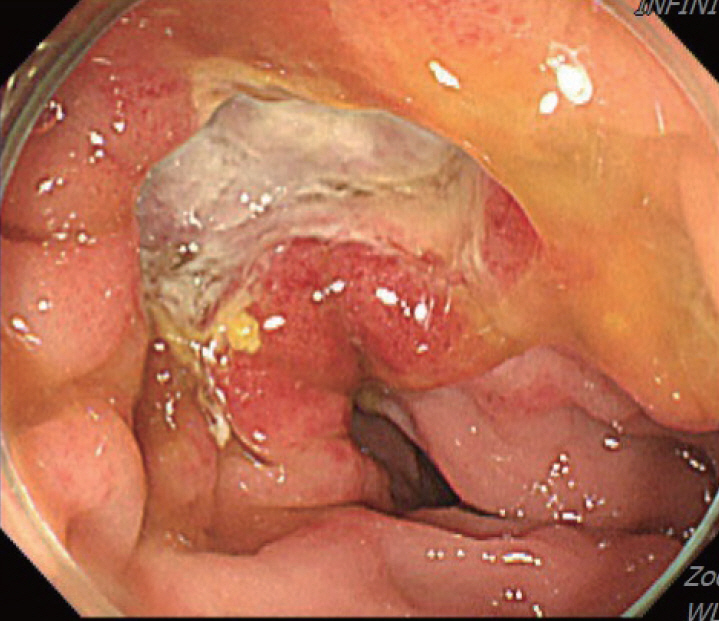

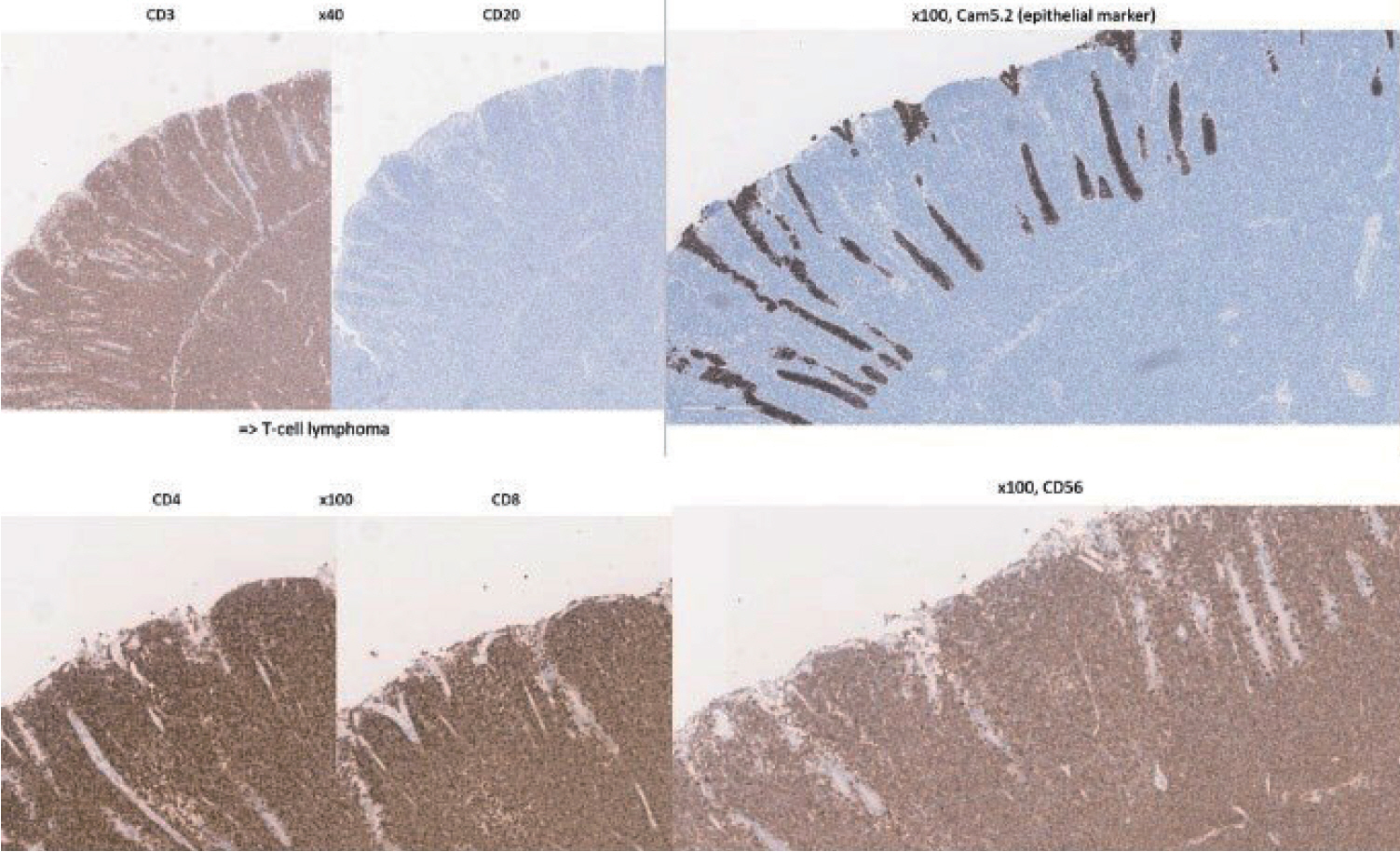

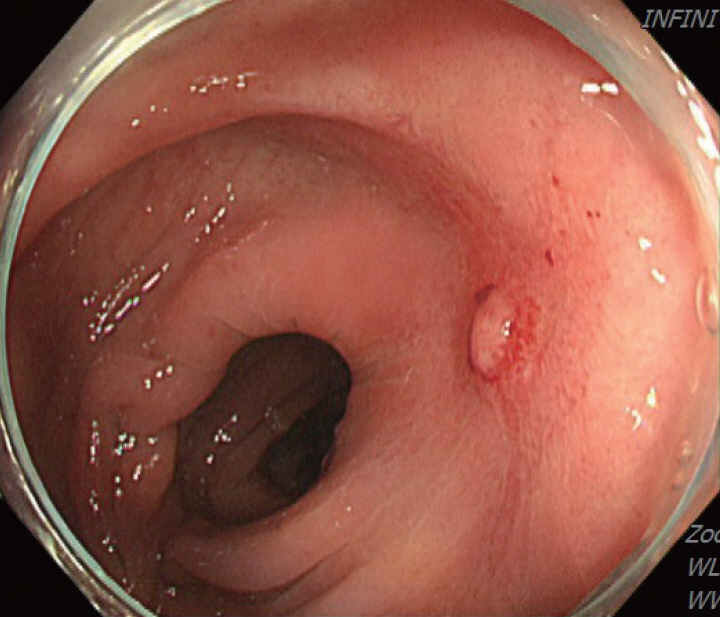

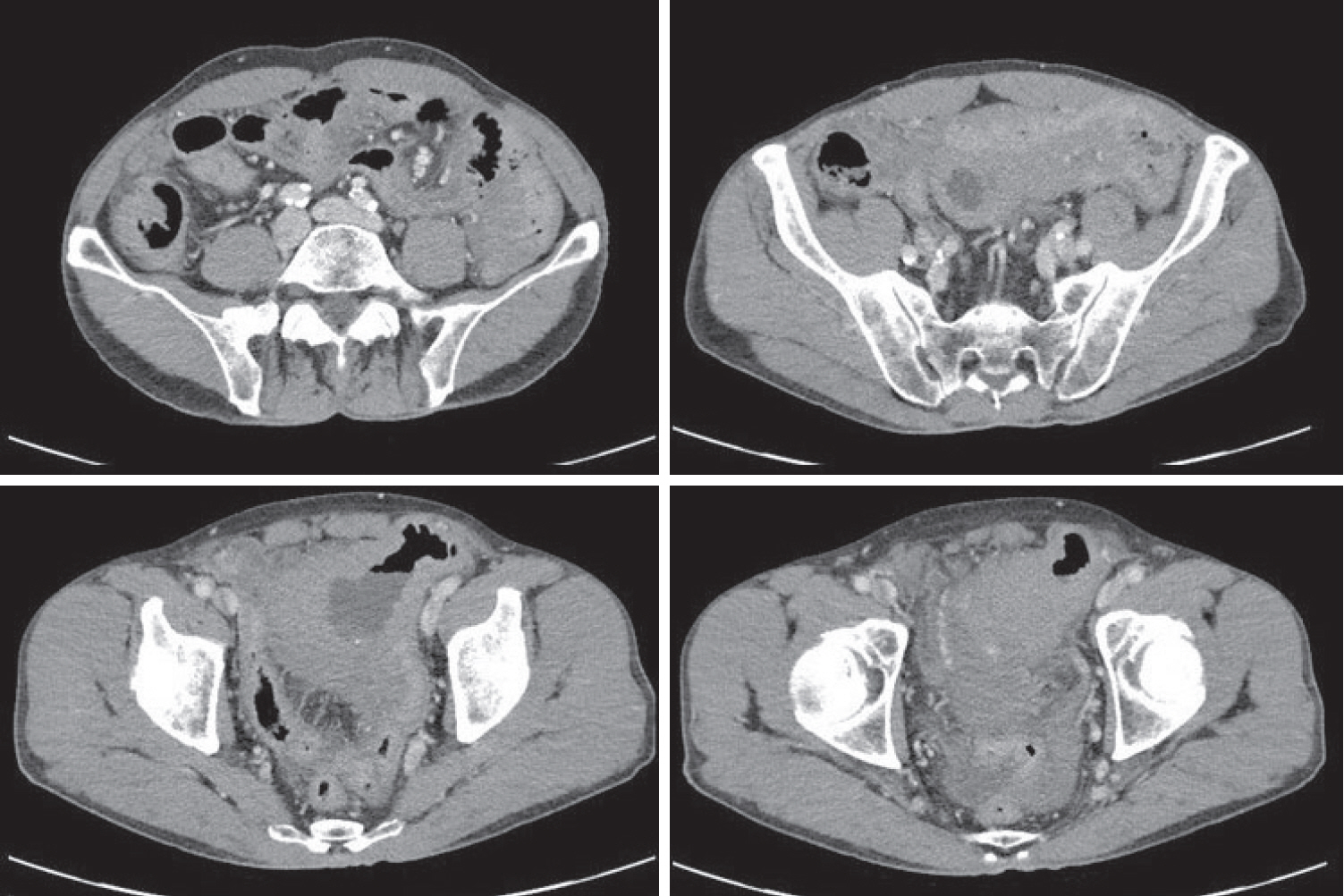

A 70-year-old male underwent sigmoidoscopy after a routine computed tomography (CT) examination, which showed thickening of the sigmoid wall (Fig. 1). Sigmoidoscopy revealed a colonic ulcer, and a biopsy was performed. The lesion was identified as a tubular adenoma; therefore, the patient was referred to the gastroenterology department for repeat biopsy and additional tests. The patient’s medical history included high blood pressure and alcoholic hepatitis. His social history showed that he drank 0.5-1.0 bottle of soju daily and was never a smoker. Information regarding his family history was excluded from the study. The patient had no gastrointestinal symptoms such as abdominal pain or diarrhea, and physical examination findings were unremarkable. Although the biopsy showed a tubular adenoma, the initial colonoscopy indicated that the gross margin of the ulcer was irregularly shaped (Fig. 2), raising suspicion for malignancy. Therefore, despite being asymptomatic, the patient was informed, and another colonoscopy was performed 2 months later. The follow-up examination revealed a scarred sigmoid ulcer located 30 cm from the anal verge, which seemed to have improved compared with the previous findings. Re-biopsy demonstrated features consistent with a simple ulcer (Fig. 3). Accordingly, we concluded that this was a benign colonic ulcer with an inflammatory and ischemic cause rather than cancer, and a follow-up CT scan was sche-duled 1 month later. At the follow-up visit 1 month later, the patient complained of abdominal discomfort after eating for a week, which had not occurred before. He denied having fever, chills, nausea, or vomiting. A subsequent abdominal CT scan showed an approximately 9-cm cavitary lesion abutting the sigmoid colon and urinary bladder dome in the small intestine (Fig. 4). This was accompanied by diffuse nodular omentomesenteric infiltration and peritoneal thickening with small ascites. Based on these findings, the patient was suspected to have a malignant tumor, such as scirrhous carcinoma, inflammatory bowel disease, peritoneal carcinomatosis, or peritonitis, and was referred to a surgeon for surgical treatment. The patient was hospitalized immediately. On admission, the patient complained of abdominal discomfort after eating, and mild generalized abdominal tenderness was noted on physical examination. He was hemodynamically stable. Laboratory testing revealed high white blood cell count of 11.45 × 103/μL (normal range, 4.0-10.0 × 103/μL) with a differential of 67.6% neutrophils (normal range, 38.0-75.0), normal hemoglobin of 16.1 g/dL (normal range, 13.0-17.0), normal platelet count of 151 × 103/μL (normal range, 150-400 × 103/μL), and slightly elevated C-reactive protein level of 7.69 mg/L (normal range, 0.0-5.0). Serum electrolyte and kidney function test results were normal. On the 3rd day of hospitalization, the patient underwent laparoscopic small bowel resection. Immunohistochemical analysis of the resected tissue showed positive staining for CD3, CD4, CD8, CD56, and CAM 5.2 (epithelial marker), and a negative staining for CD10, CD20, CD21, and CD30 (Fig. 5). Histopathological evaluation revealed infiltration by small- to medium-sized T-cell with prominent epitheliotropism, consistent with MEITL. The final diagnosis was MEITL, involving the sigmoid colon, urinary bladder, and peritoneum. Postoperatively, the patient developed persistent ileus with progressive ab-dominal distension and loss of bowel passage, necessitating a second emergency surgery on the 20th day of hospitalization. On the 25th day of hospitalization, the Hemovac drainage became purulent, blood pressure decreased, and the patient went into shock; therefore, a third emergency surgery was performed under the suspicion of bowel perforation. On the 45th day of hospitalization, the patient died of refractory septic shock, presumed to be a complication of intestinal perforation.

Colonoscopy showing a scarred sigmoid ulcer 30 cm from the anal verge, with apparent improvement compared to previous findings.

Subsequent abdominal computed tomography (CT) showing an approximately 9-cm cavitary lesion in the small intestine, abutting the sigmoid colon and urinary bladder dome.

DISCUSSION

MEITL manifests as a wide variety of gastrointestinal symptoms, ranging from abdominal pain, weight loss, and diarrhea to serious symptoms such as bleeding, perforation, and obstruction; however, no characteristic clinical symptoms have been established for this disease [6]. Only 10% of affected patients are diagnosed endoscopically, with majority diagnosed through surgery [7]. As in the present case, MEITL is often discovered accidentally without symptoms or is diagnosed when the disease has already progressed [4]. Among few papers presenting the endoscopic findings of MEITL, Tian et al [8]. described this disease as a semicircular shallow ulcer accompanied by numerous fine granules and mucosal thickening. In our patient, ulceration with associated mucosal thickening was also observed. Histomorphologically, neoplastic cells in MEITL are described as small- to medium-sized, monomorphic, and epitheliotropic lymphocytes, with pale cytoplasm and round nuclei [2]. The cells are CD3+, CD4-, CD5-, CD8+, CD56+, CD30-, MATK+, EBER-, and T-cell receptor-gamma delta+ [9]. Cytotoxic markers such as TIA-1, granzyme B, and perforin are also present [9]. Cyclophosphamide-adriamycin-vincristine-prednisone-based chemotherapy, with or without consolidative autologous stem cell transplantation, remains the mainstay of treatment [3]. In an Asian MEITL series, 72% of patients were treated with chemotherapy, whereas 58% underwent both surgery and chemotherapy [5]. However, the high rate of treatment discontinuation owing to disease progression or treatment-related adverse events continues to be a major concern in this patient population [1]. Surgical resection is necessary when symptoms appear, and approximately 50% of patients undergo emergency surgery for intestinal perforation or obstruction [5,7]. If intestinal perforation occurs, the prognosis is expected to be worse, as chemotherapy is delayed owing to peritonitis, septic shock, and multiple organ failure [10]. In the present case, treatment was likely delayed because of intestinal obstruction prior to anticancer therapy, leading to rapid clinical deterioration. Generally, the diagnostic ratio of intestinal T-cell lymphoma (ITCL) by endoscopy, including tissue biopsy, is low [11] for the following reasons: 1) tissue specimens from endoscopic biopsy are usually not sufficiently large to allow a correct diagnosis; 2) ITCL is primarily located in the submucosa and smooth muscle, and detection of the lesion through the mucosal layer from biopsy specimens is difficult; and 3) the disease can easily be overlooked because of its rarity. Therefore, tissue biopsies of ulcerative gastrointestinal lesions should be performed carefully from the base of the ulcer while considering the possibility of malignant lymphoma [11]. In this patient, despite a prompt biopsy following the incidental detection of a colonic ulcer and a second endoscopic biopsy performed shortly thereafter, an endoscopic diagnosis could not be achieved. If several deeper biopsies, including those of the submucosa, were performed at the time of the initial endoscopy, the possibility of early diagnosis may have increased. Moreover, although our patient underwent colonoscopy over a short follow-up period, the ulcer showed an atypical clinical course, appearing to improve and form a scar within a short interval. Such a presentation has rarely been reported in the related literature, and we report this case to highlight its unusual endoscopic features. Additionally, owing to this atypical pattern, careful differen-tiation from other diseases, such as benign ulcers or inflammatory bowel disease, is necessary. Our case underscores the importance of early diagnosis of MEITL, as the rapid progression of the disease can have a fatal consequence. Endoscopists and clinicians need to be vigilant in understanding endoscopic and histological findings to ensure prompt diagnosis and treatment of this aggressive disease.

Notes

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

FUNDING

None.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Bora Keum conceived and proposed this clinical case. Gyewon Park searched and reviewed reference papers and wrote the case report. Hoon Jai Chun, Yoon Tae Jeen, Eun Sun Kim, Hyuk Soon Choi, Jae Min Lee reviewed draft of the case report and provided advice on the final manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

None.