1. Czaja AJ. Autoimmune hepatitis. Evolving concepts and treatment strategies. Dig Dis Sci 1995;40:435–456.

2. Vento S, Cainelli F. Is there a role for viruses in triggering autoimmune hepatitis? Autoimmun Rev 2004;3:61–69.

3. European Association for the Study of the Liver. EASL clinical practice guidelines: autoimmune hepatitis. J Hepatol 2015;63:971–1004.

4. Alvarez F, Berg PA, Bianchi FB, et al. International Autoimmune Hepatitis Group report: review of criteria for diagnosis of autoimmune hepatitis. J Hepatol 1999;31:929–938.

5. Ngu JH, Bechly K, Chapman BA, et al. Population-based epidemiology study of autoimmune hepatitis: a disease of older women? J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2010;25:1681–1686.

6. Grønbæk L, Vilstrup H, Jepsen P. Autoimmune hepatitis in Denmark: incidence, prevalence, prognosis, and causes of death. A nationwide registry-based cohort study. J Hepatol 2014;60:612–617.

8. Floreani A, Leung PS, Gershwin ME. Environmental basis of autoimmunity. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol 2016;50:287–300.

9. Czaja AJ. Natural history, clinical features, and treatment of autoimmune hepatitis. Semin Liver Dis 1984;4:1–12.

10. Muratori P, Lalanne C, Fabbri A, Cassani F, Lenzi M, Muratori L. Type 1 and type 2 autoimmune hepatitis in adults share the same clinical phenotype. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2015;41:1281–1287.

12. Feld JJ, Dinh H, Arenovich T, Marcus VA, Wanless IR, Heathcote EJ. Autoimmune hepatitis: effect of symptoms and cirrhosis on natural history and outcome. Hepatology 2005;42:53–62.

13. Muratori P, Lalanne C, Barbato E, et al. Features and progression of asymptomatic autoimmune hepatitis in Italy. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2016;14:139–146.

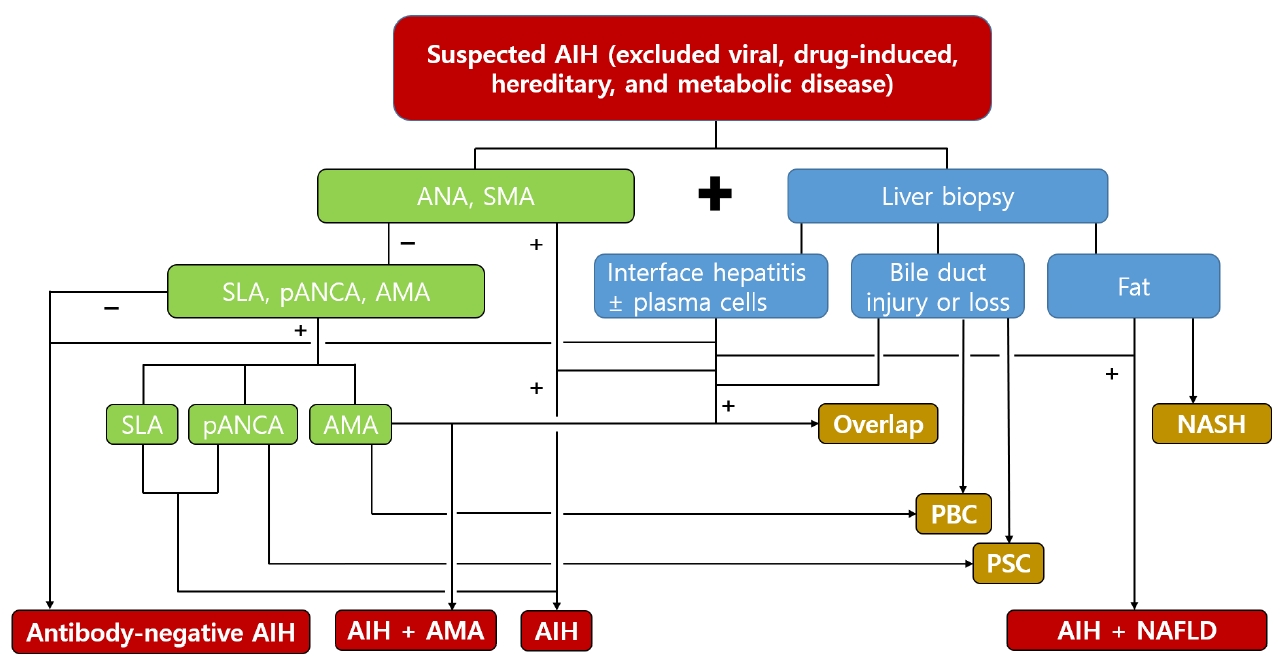

14. Manns MP, Czaja AJ, Gorham JD, et al. Diagnosis and management of autoimmune hepatitis. Hepatology 2010;51:2193–2213.

15. Mack CL, Adams D, Assis DN, et al. Diagnosis and management of autoimmune hepatitis in adults and children: 2019 practice guidance and guidelines From the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. Hepatology 2020;72:671–722.

16. Zachou K, Muratori P, Koukoulis GK, et al. Review article: autoimmune hepatitis -- current management and challenges. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2013;38:887–913.

17. Johnson PJ, McFarlane IG. Meeting report: International Autoimmune Hepatitis Group. Hepatology 1993;18:998–1005.

18. Hennes EM, Zeniya M, Czaja AJ, et al. Simplified criteria for the diagnosis of autoimmune hepatitis. Hepatology 2008;48:169–176.

19. Muratori P, Granito A, Quarneti C, et al. Autoimmune hepatitis in Italy: the Bologna experience. J Hepatol 2009;5:1210–1218.

20. Zachou K, Gatselis N, Papadamou G, Rigopoulou EI, Dalekos GN. Mycophenolate for the treatment of autoimmune hepatitis: prospective assessment of its efficacy and safety for induction and maintenance of remission in a large cohort of treatment-naïve patients. J Hepatol 2011;55:636–646.

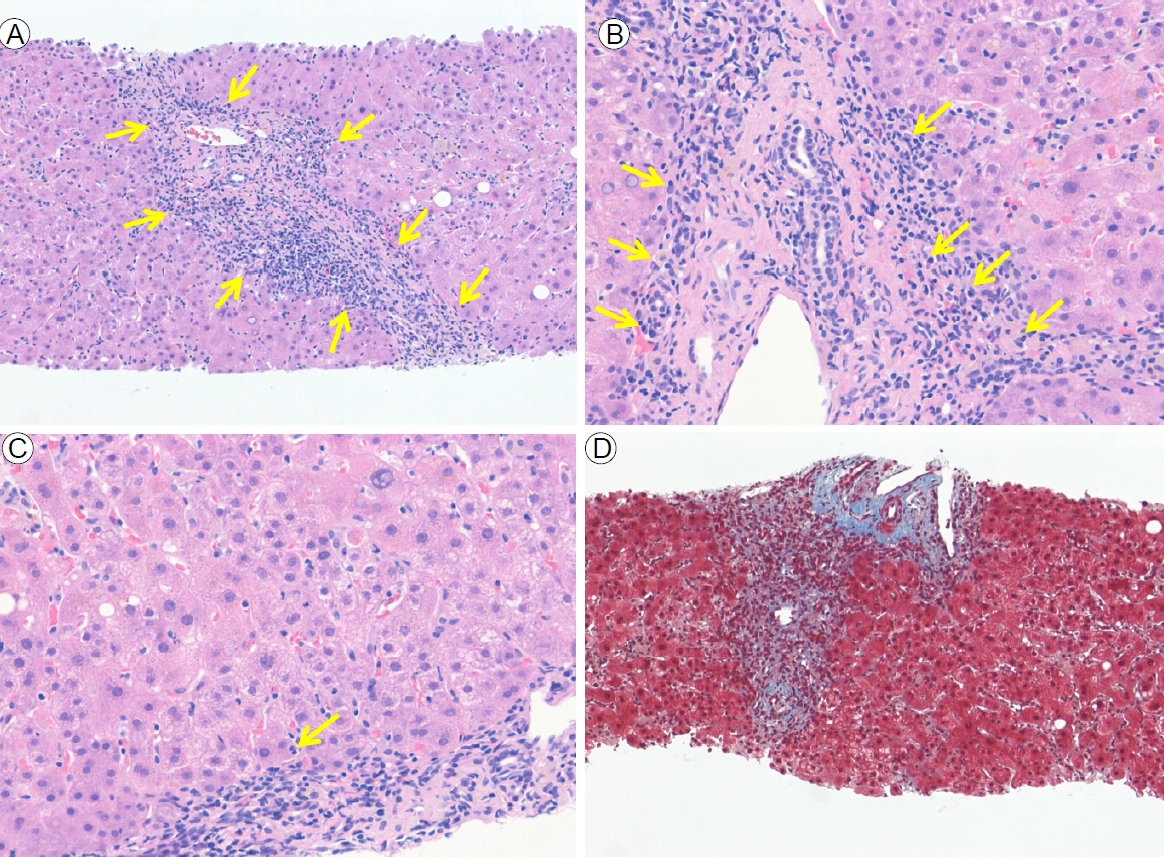

21. Fujiwara K, Fukuda Y, Yokosuka O. Precise histological evaluation of liver biopsy specimen is indispensable for diagnosis and treatment of acute-onset autoimmune hepatitis. J Gastroenterol 2008;43:951–958.

22. Yasui S, Fujiwara K, Yonemitsu Y, Oda S, Nakano M, Yokosuka O. Clinicopathological features of severe and fulminant forms of autoimmune hepatitis. J Gastroenterol 2011;46:378–390.

23. Georgiadou SP, Zachou K, Liaskos C, Gabeta S, Rigopoulou EI, Dalekos GN. Occult hepatitis B virus infection in patients with autoimmune liver diseases. Liver Int 2009;29:434–442.

24. Rigopoulou EI, Zachou K, Gatselis N, Koukoulis GK, Dalekos GN. Autoimmune hepatitis in patients with chronic HBV and HCV infections: patterns of clinical characteristics, disease progression and outcome. Ann Hepatol 2013;13:127–135.

25. Czaja AJ, Manns MP. The validity and importance of subtypes in autoimmune hepatitis: a point of view. Am J Gastroenterol 1995;90:1206–1211.

26. Czaja AJ. Performance parameters of the conventional serological markers for autoimmune hepatitis. Dig Dis Sci 2011;56:545–554.

27. Czaja AJ. Behavior and significance of autoantibodies in type 1 autoimmune hepatitis. J Hepatol 1999;30:394–401.

28. Czaja AJ, Homburger HA. Autoantibodies in liver disease. Gastroenterology 2001;120:239–249.

30. Gregorio GV, McFarlane B, Bracken P, Vergani D, Mieli-Vergani G. Organ and non-organ specific autoantibody titres and IgG levels as markers of disease activity: a longitudinal study in childhood autoimmune liver disease. Autoimmunity 2002;35:515–519.

31. Czaja AJ, Carpenter HA. Sensitivity, specificity, and predictability of biopsy interpretations in chronic hepatitis. Gastroenterology 1993;105:1824–1832.

32. Miyake Y, Iwasaki Y, Terada R, et al. Clinical features of Japanese type 1 autoimmune hepatitis patients with zone III necrosis. Hepatol Res 2007;37:801–805.

33. Balitzer D, Shafizadeh N, Peters MG, Ferrell LD, Alshak N, Kakar S. Autoimmune hepatitis: review of histologic features included in the simplified criteria proposed by the International Autoimmune Hepatitis Group and proposal for new histologic criteria. Mod Pathol 2017;30:773–783.

34. Park SZ, Nagorney DM, Czaja AJ. Hepatocellular carcinoma in autoimmune hepatitis. Dig Dis Sci 2000;45:1944–1948.

35. Wang KK, Czaja AJ. Hepatocellular carcinoma in corticosteroid-treated severe autoimmune chronic active hepatitis. Hepatology 1988;8:1679–1683.

36. Yeoman AD, Al-Chalabi T, Karani JB, et al. Evaluation of risk factors in the development of hepatocellular carcinoma in autoimmune hepatitis: implications for follow-up and screening. Hepatology 2008;48:863–870.

37. Czaja AJ. Performance parameters of the diagnostic scoring systems for autoimmune hepatitis. Hepatology 2008;48:1540–1548.

38. Yatsuji S, Hashimoto E, Kaneda H, Taniai M, Tokushige K, Shiratori K. Diagnosing autoimmune hepatitis in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: is the International Autoimmune Hepatitis Group scoring system useful? J Gastroenterol 2005;40:1130–1138.

39. Boberg KM, Chapman RW, Hirschfield GM, et al. Overlap syndromes: the International Autoimmune Hepatitis Group (IAIHG) position statement on a controversial issue. J Hepatol 2011;54:374–385.

40. Soloway RD, Summerskill WH, Baggenstoss AH, et al. Clinical, biochemical, and histological remission of severe chronic active liver disease: a controlled study of treatments and early prognosis. Gastroenterology 1972;63:820–833.

41. Cook GC, Mulligan R, Sherlock S. Controlled prospective trial of corticosteroid therapy in active chronic hepatitis. Q J Med 1971;40:159–185.

42. Montano Loza AJ, Czaja AJ. Current therapy for autoimmune hepatitis. Nat Clin Pract Gastroenterol Hepatol 2007;4:202–214.

43. Montano-Loza AJ, Carpenter HA, Czaja AJ. Improving the end point of corticosteroid therapy in type 1 autoimmune hepatitis to reduce the frequency of relapse. Am J Gastroenterol 2007;102:1005–1012.

44. Czaja AJ, Carpenter HA. Decreased fibrosis during corticosteroid therapy of autoimmune hepatitis. J Hepatol 2004;40:646–652.

PDF Links

PDF Links PubReader

PubReader ePub Link

ePub Link Full text via DOI

Full text via DOI Download Citation

Download Citation Print

Print